- Home

- Mark Frost

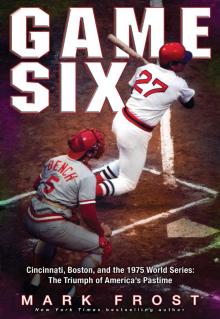

Game Six

Game Six Read online

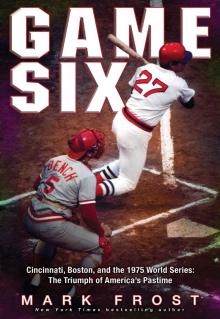

Game Six

Cincinnati, Boston, and the 1975 World Series:

The Triumph of America’s Pastime

Mark Frost

Luis Tiant and Pete Rose, the first pitch, Game Six

Courtesy of Getty Images.

To Vin Scully

Baseball’s master storyteller

Contents

Prologue

A NEW BASEBALL, SUBMITTED TO CARING AND REGULAR maintenance, might…

One

THE SUN ROSE ON BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS, AT 7:03 IN THE…

Two

BEFORE THEY MOVED DOWNSTAIRS FOR THE PREGAME ceremonies, the two…

Three

FOR GEORGE “SPARKY” ANDERSON, HALF OF THE JOB OF managing…

Four

ON THEIR WAY UP TO THE BOOTH TO PREPARE FOR…

Five

FOR ALL THEIR SUCCESS IN 1975, WINNING ONE HUNDRED games…

Six

BEFORE THE WORLD SERIES BEGAN IN 1975, THE CINCINNATI Reds…

Seven

THAT FIRST “WORLD SERIES” IN 1903, BETWEEN THE BOSTON Americans…

Eight

AFTER EACH OF THE FIRST TWO SEASONS HE PITCHED FOR…

Nine

SUGGESTIONS THAT THE FIRST GAME OF THE FIRST “World Series”…

Ten

LUIS TIANT AND HIS WIFE, MARIA, HAD DECIDED DURING the…

Eleven

WHEN FIDEL CASTRO FINISHED READING SENATOR Brooke’s letter about Luis…

Twelve

AMAZING AS LUIS TIANT’S COMEBACK FOR THE RED SOX had…

Thirteen

UP IN THE NBC BROADCAST BOOTH, APPEARING ON CAMERA for…

Fourteen

AFTER THEIR VICTORY IN THE FIRST WORLD SERIES IN 1903,…

Fifteen

HALFWAY THROUGH THE SEVENTH INNING OF GAME SIX, the contrasting…

Sixteen

HE’D THROWN 110 PITCHES IN THE GAME NOW. HIS FASTBALL,…

Seventeen

THREE WEEKS BEFORE GAME SIX THE ENTIRE SPORTING world had…

Eighteen

RED SOX FANS—CONNOISSEURS OF DESPAIR—HAD A NEW flavor to reckon…

Nineteen

AFTER MIDNIGHT NOW, THE BRIGHT FULL MOON HUNG in a…

Twenty

TO LEAD OFF THE BOTTOM OF THE ELEVENTH, RED SOX…

Twenty-One

IT WAS 12:34 ON WEDNESDAY MORNING, OCTOBER 22, NOW, 241…

Game Seven

Afterward

Appendix

Searchable Terms

Acknowledgments

Other Books by Mark Frost

Copyright

PROLOGUE

Georgie was always brave enough to do the right thing.

ROD DEDEAUX

South Central Los Angeles, 1943

A NEW BASEBALL, SUBMITTED TO CARING AND REGULAR maintenance, might last an entire summer on the Rancho Playground, and there one lay in the dirt of a vacant lot, an unclaimed jewel, just outside the right field fence. The boys all jumped at it, but the smallest and quickest of them grabbed it fast, and to the others’ shock withheld it.

Came from the ball field, said George Anderson, nine. Ain’t ours. We gotta give it back.

Poor kids, toughened by poverty and the Depression, weren’t used to forgoing found treasure for principle, but George, a year removed from Bridgewater, South Dakota, and outdoor plumbing, and tougher already than most, stood up to them. He walked back around the fences to the diamond, where the uniformed college boys were practicing on Bovard Field, picked out the older man who seemed to be in charge, and held up the ball.

This yours?

The coach stared at him with—what was that, shock or amusement?

Found it lying out past the fence.

Where you live, son?

Couple blocks, said George, and held it out again, thinking maybe this guy had forgotten the main point.

The coach, Rod Dedeaux, took the ball this time and studied the youngster for a moment.

What’s your name, kid?

George Anderson.

George, how’d you like to be my batboy?

Diogenes, the eccentric Greek philosopher-cynic, who famously searched throughout Athens for a single honest man, claimed he never found one, but Rod Dedeaux just had. And so, for the next seven years, George Lee Anderson worked as the batboy for the University of Southern California’s baseball team. The pay wasn’t much; what little there was came from Dedeaux’s pocket, although anything was a help to the hard-pressed Anderson family: George’s father, Leroy, a painter and onetime semi-pro catcher back in South Dakota, had moved to Los Angeles to work the wartime shipyards and feed his four kids.

Raoul Martial “Rod” Dedeaux, like Leroy Anderson and most of the boys in the generation that came of age during the Babe’s heyday, grew up on dreams of playing major-league baseball. Unlike most, Dedeaux had the goods: As the captain and star shortstop for USC, six months after his twenty-first birthday Dedeaux signed a contract with the Brooklyn Dodgers, played that summer for their minor-league affiliate in Dayton, Ohio, and earned a late-season call-up to the National League club.

A lot of promise, this Cajun kid, his longtime mentor and Dodgers manager, Casey Stengel, told the Brooklyn Eagle. Exceptional glove, live bat; nothing but blue sky.

Just starting his legendary career as a manager, Stengel had first scouted Dedeaux in high school and thought so much of the young prospect he paid Rod’s $1,500 signing bonus out of his own pocket. On September 28, Stengel penciled Dedeaux in at shortstop against the Phillies, and he lived up to Stengel’s hype in his first professional start, going 1–4 and driving in a run. The game itself, the back end of a meaningless doubleheader at Ebbets Field between two clubs long out of the pennant race, was played in front of exactly 124 paying customers and halted on account of darkness after eight innings, in a 4–4 tie.

The Dodgers never finished that game, and neither did their new shortstop; he never got the chance. After only his second professional game, Dedeaux’s major-league career ended with terrible suddenness when he learned that a violent missed swing he’d taken had cracked a lumbar vertebra. He returned to Los Angeles and, using the last $500 of his bonus money, founded a trucking business with his father that succeeded so spectacularly he would never worry about a payday for the rest of his life. The college coach he’d played for at USC entered the navy in 1942 when the war began, and recommended Rod to take over his position with the team. Unfit for military service because of his injured back, Dedeaux took the job, but would accept only a token salary of $1 a year; and that spring, young George Anderson walked onto his diamond. During the off-season winter months of professional baseball, when he was back home in Southern California, Dedeaux’s old mentor Casey Stengel became a constant presence on the USC practice field as well. The “Old Perfessor” managed Oakland in the Pacific Coast League after the war, before his glory years with the Yankees began in 1949, but for all the fun sportswriters made over the years of his famously fractured English, Stengel was as knowledgeable about the game as any man alive. (Dedeaux insisted he always understood everything Casey said, admitting, “which sometimes worried me.”) For his batboy George Anderson, the chance to listen to the old fella talk baseball every day was, as Dedeaux years later described it, “like sitting at the feet of Socrates…if George had only known who Socrates was.”

During his final season with the team, Anderson worked the game when the Trojans won their first College Baseball World Series for Rod Dedeaux in 1948. Before he retired thirty-eight years later, Rod Dedeaux would go on to capture ten more NCAA championships, winning 1,332 games along the way, more than any baseball coach in college history. He would also manage two American Olympic teams and train the actors in the m

ovies Field of Dreams and A League of Their Own to look like major leaguers. Forever grateful for the early faith Casey Stengel had shown in him, Dedeaux later became the Old Perfessor’s legal protector during his long and troubled dotage. Dedeaux never asked for or accepted more than that $1-a-year salary from USC, and became as beloved and celebrated a father figure inside his sport, if less well known outside of it, as John Wooden was in his, across town at UCLA. In the course of his joyful life’s work, Rod Dedeaux recruited, taught, and nurtured dozens of remarkable young talents who would go on to play and star in the major leagues.

That scrappy little batboy Anderson never played a game for USC or any other college; higher education wasn’t in the cards for Georgie. He had no taste for academics, but his years with Dedeaux gave him a tireless appetite for hard work, and the wisdom and enthusiasm of a great teacher soaked deep into his character. Using the skills and competitive fire he’d honed at Dedeaux’s side, Anderson earned All-City honors twice playing shortstop for Dorsey High, a team that won forty-two games in a row on its way to consecutive championships, a record unmatched in Los Angeles to this day.

Harold “Lefty” Phillips, a former minor-league pitcher and then big-league scout who covered Southern California, took an early interest in George Anderson. Lefty befriended the boy, intrigued by his feral intensity on the field and, unheard of in a kid his age, his insatiable thirst for knowledge about the guts of the game. On Phillips’s recommendation, the Brooklyn Dodgers signed Anderson to a minor-league contract less than an hour out of Dorsey High. He cashed his bonus check—a $3,000 windfall—and the Dodgers dispatched him to their developmental farm team just up the coast in Santa Barbara. George Anderson’s dreams of playing professional baseball were right on track; given his lack of interest in all things academic, they needed to be.

A few years later, in 1955, the third season of George’s wayward journey toward the big leagues, his team’s radio announcer in Fort Worth commented on what had become a fairly common scene that summer: Anderson, hopping mad after a questionable call at second, going off on an umpire.

The sparks are flying again tonight.

Before he knew it, George “Sparky” Anderson had been stamped with what every bona fide major leaguer needed to make it to the top: a nickname.

Nicanor del Campo, Havana, Cuba, 1958

THE OLD MAN didn’t want to see his son pitch. Why encourage him down this path where only disappointment and heartbreak waited? Let the boy finish his education, go to trade school, learn a craft or profession, something he could put his hands around besides a bat or ball.

Why did we take the trouble to send him to that private school, Isabel? Why did we teach him to speak English?

The first games his son played didn’t even involve a real ball, but a stone wrapped in newspaper—or a cork freighted with nails—stuffed into a cigarette box, then smashed as close as possible to round and covered in Band-Aids. An old broom handle for a bat. When there was almost no money to eat, real equipment remained miles out of reach, but all the kids played just the same. Baseball had taken root on the island in the second half of the nineteenth century, not long after finding life in the United States, but it quickly permeated the bloodstream of Cuban culture, becoming the national sport and spreading from there throughout the Caribbean, then into Mexico and from there into Central and South America.

Baseball is no life for him. No life for any man.

El corcho, they called the street game. Cuban stickball. Young Luis still hit that makeshift pelota out of sight. And when he was pitching? No chance. Just take your cuts and pray he didn’t drill you in the ribs.

Truth be told, everything Luis did, from cards to marbles, seemed exceptional, effortless, but he carried his talents so lightly, with such warmth and modest grace, that he inspired only affection in his many friends, not envy. And he always found a way to make you laugh, with that scratchy high-pitched voice, the joke you never saw coming, like that crazy curveball of his. You didn’t mind losing to a boy like this—although you always did—but with his generosity of spirit you somehow only liked him more for it.

Once he reached the required age for Little League and took the mound as a pitcher, he dominated kids three and four years older; they could hardly even see his fastball. Officials refused to let him pitch in night games, for fear batters wouldn’t pick up a pitch coming at their head under the insufficient lights. From the start, like so many other boys around the Americas, Luis Clemente Tiant began early to dream about the major leagues. But young Luis stood apart in more ways than just his talent: His Old Man had already lived the same dream.

Luis Eleuterio “Lefty” Tiant played professional baseball for twenty-two years, from 1926 to 1948, the last fourteen in the American Negro Leagues, where he won more than one hundred games, including two pennants and a championship, for the New York Cubans. Historians believe he may have been the best left-hander in the Negro Leagues’ existence, a master of the art of pitching with impeccable control. A tall, elegant splinter of a man, they called him “Sir Skinny.” His screwball—what he called his “drop” pitch—falling low and away from right-handed batters, was said to be even nastier than that of the New York Giants’ acknowledged junk-ball genius, Carl Hubbell. Tiant developed such an extraordinary pickoff move to first base that he once nailed a runner there and so baffled the batter with his motion that the man swung at a phantom pitch, which started an argument about whether he’d struck out for a double play. Tiant faced most of the major leagues’ Hall of Fame contemporaries at one time or another in exhibition games, and handled them all, including Babe Ruth and Mel Ott; Lefty held the Babe to a long single in six at bats, and Ott went hitless.

Consider the price he paid for that dream. Although they often played in Yankee Stadium and the Polo Grounds—when their white teams were away—the New York Cubans never had a home stadium, so they played their entire season on the road; a team of émigrés from the island, most of whom didn’t speak English, the Cubans occupied an even lower social caste than the American blacks they usually competed against. Seven months a year away from his wife and only son, in the shadows of an unfamiliar culture, suffering the worst of Jim Crow apartheid in los Estados Unidos—third-class trains, broken-down buses, and segregated rooming houses—for his troubles, Sir Skinny never collected more than $1.50 a game. And by the time the Lords of Baseball decided to let Jackie Robinson take the field in a Brooklyn Dodgers uniform alongside Caucasian players, Luis Tiant Sr. was forty years old.

And at that age, in 1947, he put together one last extraordinary season: 10–0 with three shutouts and two victories in the Negro League World Series to lead his Cubans past the Cleveland Buckeyes. Then, his pitching arm beaten dead, the Old Man called it quits and went home to the island for good. He was widely recognized as the greatest pitcher—perhaps the greatest athlete—ever in Cuban history, and all he had to show for all those years was enough to buy half interest in a truck with his brother-in-law. The great El Tiante moved furniture for a living now, his wife, Isabel, worked as a cook, and they had scraped and saved and sent their only child to that private school where they taught him English so that he could one day build a better life.

Baseball couldn’t give his son anything. The Old Man knew it every time he passed a mirror. He was only fifty-two, but with his mournful, deeply etched face and drugstore false teeth, he looked seventy.

Just watch him play, Isabel insisted. Give him that much.

You don’t know about baseball, he told her. I don’t want him to be treated like I was, to be persecuted and spit on like I was in America. And for that he will have to give up his friends, his family, his country.

But this is what he wants, she said. Things are different now in America, even in baseball. He deserves a chance, we owe him at least that much.

Their son, eighteen years old now, had pitched his way onto a Havana All-Star team, competing against the best players from the other three provinces of C

uba. So much excitement around the city and in the newspapers about this Second Coming of El Tiante: Could the son possibly be as good as, or even better than, his father? There would be scouts in the stands, from both Mexico and America. One of them, thirty-five-year-old Bobby Avila, had once been a batboy for Señor Tiant’s old Negro League team. A generation younger, Avila had lived a different dream after Robinson broke the color barrier, and gone on to become one of major-league baseball’s first great Latin players—an American League batting title in ’54, three times an All-Star at second base for the Cleveland Indians. Now a national hero in his native Mexico, when he played winter ball in Cuba Bobby Avila had stayed in touch with the Old Man and followed with interest young Luis’s development since he was a little boy.

From the bus stop behind the factory you could see the playing field in Cerro Stadium. Señor Tiant stepped off the bus just as the game started and watched from there, hoping he wouldn’t be noticed. He saw his son throw an overpowering game.

He has so much to learn. That move to first base, it could be much better. The leg kick, if he just hesitated a little, yes, I could show him that. Maybe he comes a little too much sidearm, across his body, that could hurt him eventually. If he mixed up his delivery, changed the angle, came overhand with that curve, then sidearm with the fastball. He throws hard, yes, but throwing isn’t pitching…

But, Madre de Dios, he’s a pitcher.

Of course Luis knew he had been there from the start. Spotted him hiding near the bus stop on his first trip out from the bench. Not much escaped his deceptively sleepy eyes. But he didn’t look that way again, wasn’t going to let his father know he knew. Luis left behind his kind and gentle nature when he walked between the lines; he had work to do out here. These batters deserved no respect, they were only there to take money from his pocket.

Rogue

Rogue The Second Objective

The Second Objective Alliance

Alliance Twin Peaks: The Final Dossier

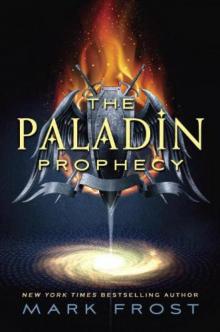

Twin Peaks: The Final Dossier The Paladin Prophecy

The Paladin Prophecy Game Six: Cincinnati, Boston, and the 1975 World Series: The Triumph of America's Pastime

Game Six: Cincinnati, Boston, and the 1975 World Series: The Triumph of America's Pastime The List of Seven

The List of Seven The Autobiography of FBI Special Agent Dale Cooper

The Autobiography of FBI Special Agent Dale Cooper The Six Messiahs

The Six Messiahs The Secret History of Twin Peaks

The Secret History of Twin Peaks Paladin Prophecy 2: Alliance

Paladin Prophecy 2: Alliance Game Six

Game Six